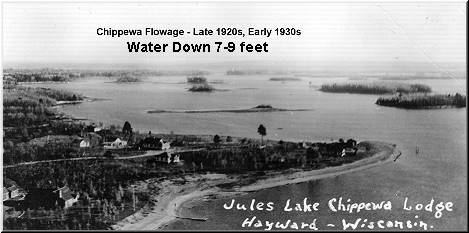

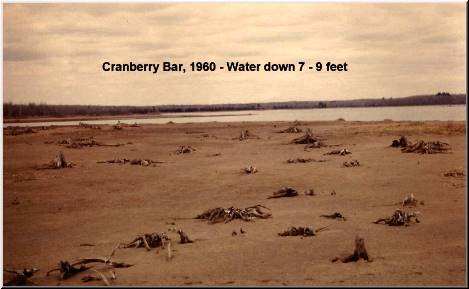

Obviously, extreme drawdraws like we

had during the early years (the 1920s and 30s) had some serious

consequences, isolating fish in small pools or sections of the

Flowage where they died due to a lack of oxygen. In some

instances, men like John Weidman were hired to dig trenches from

some of these pools so they would connect with deeper water

sections and streambeds to allow the fish to migrate to safety.

These drawdowns were most extreme in 1925, 1926, 1928, and 1931

when the Flowage was dropped more than 24 feet, nearly back to

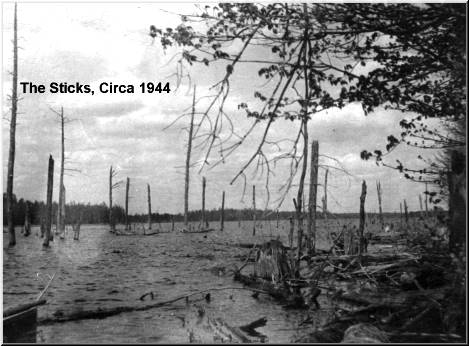

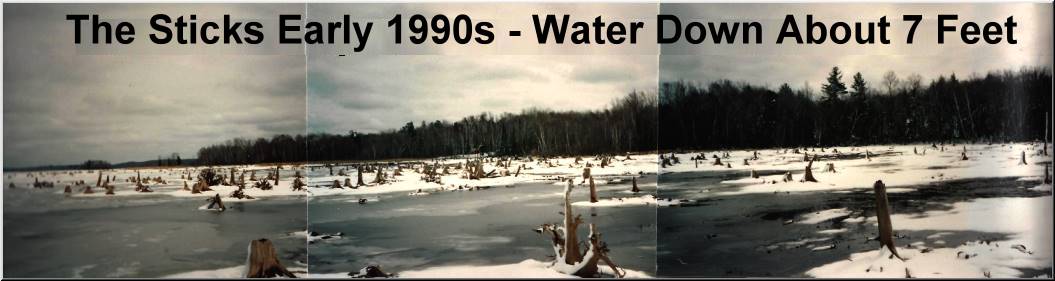

the levels of the original river and lake system. After 1939

consistent extreme drawdowns were halted; between 1940 and 1971

drawdowns fluctuated between 11 and 23 feet down (averaging

around 15 feet); and from 1971 thru 1997 more moderate drawdowns

in the 8 to 14 foot range were utilized. The moderate drawdowns

of this later period proved to be very beneficial to the health

of the Flowage’s fishery while at the same time not being so

extreme as to isolate and kill significant numbers of fish.

Arthur Oehmcke, one of the State’s

most well-known and accomplished fish culturists, was present on

the Chippewa Flowage working its hatchery at the Winter Dam

during the late 1930 and 1940s and remained intimate with the

fishery of the Flowage during the years that followed. Although

Oehmcke agreed that it was a good thing that the extreme

drawdowns of the early years ceased, he empathically stated that

the more moderate drawdowns were good for the Flowage in that

exposing the bottom sediments created oxidation which in turn

released the much needed nutrients into the ecosystem of the

Flowage. These nutrients, forms of zooplankton known as

crustaceans - more specifically referred to as "water fleas"

(Daphnia, Cyclopes, and Polyphemus) - are the critical forms of

feed that newly hatched fry need to survive for the first two

weeks of their lives after they lose their food sac and become

free swimming.

These free swimming fry are too small

to subsist on small minnows, rather they must forage on the tiny

water fleas - which are the size of pepper - to survive. For

decades, this is what gave the Chippewa Flowage an enormous

edge, especially to it musky and walleye recruitment numbers.

Because of the drawdowns and the resulting oxidation and

significant nutrient releases of water fleas every year, the

Chippewa Flowage had some of the highest recruitment numbers of

musky and walleye in the State. During the past 10 or 15 years

however, these recruitment numbers have been low for both musky

and walleye…. very likely because their newly hatched fry have

had much less natural food (water fleas) to eat.

Naturally, there is pro and con to

whatever drawdown that is utilized; however, I firmly believe

that the pros greatly outnumber the cons regarding a moderate

Winter drawdown. Years ago, during the more moderate

drawdowns, in addition to having higher populations of young

musky and walleye, the crappie averaged much larger and the

bluegill population was considerably less…. a much better

circumstance to sustaining healthy walleye and musky

populations. Keep in mind: although bluegill are fun to catch,

allowing a lake to overpopulate with stunted growth bluegill can

seriously threaten newly hatched walleye and musky fry.

As far as bass go: the smallmouth bass

seem much less affected by drawdowns as they seek out deeper

water during such periods. Largemouth, however, are more likely

impacted by moderate drawdowns so their numbers would also

likely drop to some degree. But remember, because (like the

bluegill) they are not a friend to walleye populations, it is

best for the health of the walleye fishery - and probably the

musky fishery as well - to keep largemouth populations in check.

The benefit of reducing largemouth bass populations though, is

that it is likely to improve the size structure and growth

potential of the bass that remain.

So the stage is set with this Winter’s

drawdown to help increase the musky and walleye recruitment

numbers in two ways: first, to give our newly hatched musky and

walleye fry much more food to eat and, secondly, reducing the

number of predators that are waiting to gobble them up.

Much has been said about the benefits

of a Winter drawdown combating and reducing the ever growing

problem with Eurasian milfoil, an invasive species. The

abundance of Eurasian milfoil is a concern because it negatively

impacts boating and fishing and – as it dies out under the ice

during the Winter – contributes to increased oxygen depletion

and, ultimately, increased fish kills. The greater the weed

build up that a body of water has, the more likely it is to have

oxygen deprivation issues during the coming Winter season. So it

is in the best interest of the Chippewa Flowage to do our best

to combat the excessive milfoil growth.

Eurasian milfoil is not the only

undesirable weed in the lake. There are many other types of

"junk weeds" that negatively affect the fishery as well.

Furthermore, excessive weed buildups can form a matt of decaying

material on the lake bottom and increase the rate at which the

bottom will muck up or silt over – a situation that can not only

speed up the aging process of a lake but seriously threaten the

viability of good spawning habitat.

Thankfully, because the Chippewa

Flowage is a reservoir and its water level can be controlled,

there is something we can do about this weed issue. By allowing

a moderate drawdown of 8 to 10 feet, most of the lake bottom

that grows the Eurasian milfoil (and other "junk weeds") will be

exposed and the Winter’s hard freeze will greatly contribute to

freezing out the roots of the Eurasian milfoil… giving milfoil

much less of a presence during the following summer season.

Although drawdowns on the Flowage have proven to greatly reduce

Eurasian milfoil and other "junk weeds" during the following

season, it has done little to harm the good quality weeds that

we like to see. Quite the contrary, after a moderate drawdown we

usually have very good quality, desirable weeds but yet much

less Eurasian milfoil and "junk weed".

The upside to having a moderate

drawdown in the 8 to 10 foot range is that a high percentage of

the Eurasian milfoil growth will not even be in water as it

decomposes, rather it will die sandwiched between the ice cover

and the lake bottom. Therefore removing these dying weeds from

the "water equation" greatly reduces potential oxygen

deprivation and thus minimizes potential fish kills.